Maria Majsa

Hammersmith Palais, London 1980

Only my dreams satisfy the real need of my heart

The week I turned eighteen, I got on a plane to London. There was stuff going on at home I needed to leave behind, though at the time I didn’t appreciate the way that stuff has a tendency to come with you. Wherever you go, there you are.

A relative gave me an old jigsaw puzzle with a faded picture of Trafalgar Square on the box when I was nine. The hours I spent poring over crumbs of colour – turquoise for the fountain, red for the doubledecker bus – clearly sowed a subconscious seed of London as a happening metropolis [with Nelson’s Column apparently its epicentre]. Unlike the picture on the box, however, the lure of London didn’t fade for me over the years, it just got stronger.

Huddled round the stereo in his room as teens, my brother and I would kindle a lifelong crush on indie music; sharing airmailed copies of the NME, discussing the post-punk music scene. But mostly we listened, safely out of our father’s reach, to music that was new. And definitively ours. London was the place where all of this happened; it was the hub of youth culture, the hallowed stage where the bands all played. I had as much to run to as I had to run from.

It felt quite brave striking out on my own for the other side of the world. But then, stumbling around in a haze of jetlag and elation days after arrival, I was cornered by a couple of wideboys in cheap suits. Huge, blunt and intimidating, they talked fast, stole my money and left me in the street. I have never felt more clueless or unworldly than I did as I watched them walk off, laughing.

Everyone seemed so streetwise. All I had was chronic uncertainty and no sense of direction. I could have easily come unzipped at that point; instead I resolved to get a firmer grip on things. Each day I shoved on my Docs and headphones and walked the streets. I learned how all the boroughs interconnected like a giant jigsaw, mentally ticking off the sights: saucy Soho, stately Knightsbridge, the grimy Houses of Parliament and the sluggish, tea-coloured Thames. Everything was smaller and dirtier than expected and most Londoners, it seemed, would go miles out of their way to avoid talking to a stranger.

For three weeks I wandered the city like a ghost, as though the other me from far away had died and these streets were my heaven. I got a job and moved from squalid hostel to squalid bedsit. I built myself a defensive fortress: hands in pockets, head down, walkman on. I went to gigs alone, disappearing into the music and the crowd. And though I adopted the same frazzled, big city ennui I saw in other faces every day, it was never the real me.

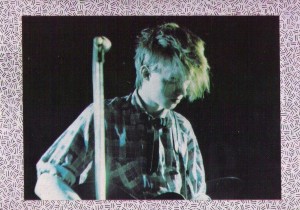

A few weeks before Christmas, I saw the Undertones at the Hammersmith Palais. They were supported by a young Scottish band I’d never heard of whose lead singer wore socks and sandals and a floppy fringe. He introduced himelf as Edwyn. He seemed nervous. I sympathised.

Orange Juice were new in town, that much was obvious. And so I listened, politely at first. Their sound was bright and melodic with a hint of something steelier just beneath. I’d never heard a rhythm guitar work quite so hard before – literally double timing the beat. Between songs, Edwyn filled the gaps with chunks of faltering banter.

Their lyrics were disarming, straight from the heart. And then there was Edwyn’s voice. He had a particular vocal catch; a sort of tremulous hesitation, which meant he didn’t always hit the note he was going for. Not that it mattered. What did matter was the way he kept at it so valiantly. It gave the performance an element of jeopardy. There was something heroic and authentic about the way he offered himself up like that, imperfections and all.

Their set progressed and I noticed that sense of buzzy intensity you get when you’re making an important discovery. After all the attitude and swagger of punk, here was a band with the courage to be vulnerable. And while admitting to vulnerability is never comfortable or easy, it is necessary for real human connection. So when Edwyn sang: Worldliness must keep apart from me, I felt an instant affinity. And a massive sense of relief.

The glow had barely faded on this feeling, when something ugly began to kick off up the front. A bundle of skinheads had noticed Edwyn’s choice of footwear and they were giving him hell. Ignoring them didn’t seem to be working and for a while it looked as though they might derail the whole gig. I hated to think what might have happened if Edwyn had met this lot on a darkened street instead of a well-lit stage and I wondered uneasily how he was going to deal with them.

Outwardly he remained calm, though I could see from where I stood that he was shaking. I don’t recall exactly what he said to them, but I do remember the song he played straight afterwards was Falling And Laughing: You must think me very naïve, take it as true, I only see what I want to see.

This gentle, swooning track was the perfect antidote to lumbering thuggishness and a fitting introduction to the Sound of Young Scotland. It certainly left behind something thoughtful and gracious in the air that wasn’t there before: So I’m standing here so lonesome, what can I do, but learn to laugh at myself.

© Maria Majsa

Wonderful story Maria. I loved OJ at that time too but never saw them live – wish I had. I remember reading somewhere that Edwyn and co were always getting abused on stage in Glasgow for the way they looked so I guess they were used to it, which makes it no less scary when it happens. They were courageous, and so were you for taking on London at that age. Thanks for this.

Thanks so much, Nick. Not sure if I was courageous or just young and clueless at the time. One of the best things about discovering OJ so early, was being able to follow their trajectory through the years. In the late 80s I saw Edwyn do a solo show at the Town & Country and it was lovely to compare his easy, consummate performance with that first nerve-wracking show at the Palais. He’d come such a long way and I’d watched it happen.

Xm

Another evocative story Maria – I can see you there – quietly brave and

taking it all in – thinking all the time – I’ve seen this in your kids over the years. Send me the next one pronto!

Aw thanks B. You lovely creature. Next one almost done. Will send it when it is.

mx